Nuisance Flooding

There is no shortage of reasons to live in coastal North Carolina: beautiful views, ocean breezes, and unmatched recreational opportunities, among others. However, coastal communities face unique challenges, one of which is becoming a real nuisance. More specifically, the problem is nuisance flooding.

What is nuisance flooding?

Nuisance flooding, also called tidal or “sunny-day” flooding, refers to a specific intensity of flooding as determined locally by the National Weather Service (NWS), a branch of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In order to properly inform the public about the extent and impact of impending floods, NWS categorizes floods as minor, moderate, or major, and issues an advisory to the communities which will be affected.

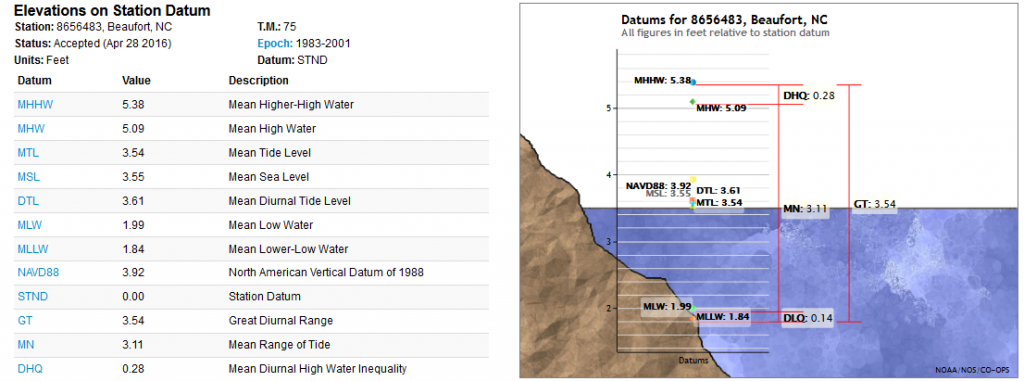

To classify floods, NWS sets elevation thresholds for each. Minor and nuisance flooding is therefore that which meets or exceeds the threshold for minor flooding that is set by NWS.1 On the coast, flooding is obviously greatly impacted by tidal dynamics (for example, typically a storm which hits the coast at high tide will cause more flooding than if it were to arrive at low tide). It is difficult to understand nuisance flooding without understanding tidal datums.2 In essence, a tidal datum is a measurement of elevation associated with a specific phase of the tide, from which local water levels, and changes in them, can be assessed.3 Using gauges and other surveying equipment, NWS calculates these datums, upon which they base their assessment of what constitutes a minor as opposed to a major flood. Tidal datums are essentially a way to link a measurement of elevation to an area’s tidal cycle. All tidal datums are averages calculated over a set 19-year period called the National Tidal Datum Epoch (NTDE). All of the country’s tidal datums and heights are averaged over this period to make them more uniform and to reduce the impact of localized fluctuations, such as those related to topography and weather.4,5 For example, the tidal datum mean sea level (MSL) is an average of hourly water heights, including both low and high tides. However, MSL is a relatively broad assessment of water level since it takes into account all water heights. Other tidal datums include Mean High Water (MHW), Mean Low Water (MLW), and their companion values Mean Higher High Water (MHHW) and Mean Lower Low Water (MLLW). Although the last two terms may sound redundant, they address the fact that many coastal areas experience mixed tides, where the second low and high tide of each day vary dramatically from the first.6

Once NWS calculates tidal datums for a given coastal area, these elevations can be used as reference points by which to set minor, moderate, and major flooding thresholds. These thresholds allow scientists and citizens to measure the frequency of nuisance flooding in that area.

This screen grab from NOAA’s website lists the values of multiple tidal datums as measured at a water level station in Beaufort. You can learn more about the tidal datums for specific areas and cities by visiting NOAA’s Tides and Currents website and selecting a station.

What are the impacts of nuisance flooding?

Although classified as “minor” or simply labeled as a nuisance, this type of coastal flooding can have serious impacts on coastal communities. Tidal flooding can pollute drinking supplies via saltwater intrusion, shutter businesses, flood homes, close roads, and cause drainage and storm-water systems to be overwhelmed or back up completely, leading to streets being flooded with excess seawater. Infrastructure which is not designed to withstand saltwater can corrode and potentially cease to function.7

What does climate change have to do with it?

Although climate change will impact coastal communities in a variety of ways, one of the most significant effects is from sea-level rise. Globally, sea levels are rising due to the expansion of seawater as it absorbs the heat trapped by the atmosphere and accepts meltwater from land-based ice. The global mean sea level has increased by about 3 inches since 1993, and has been increasing more rapidly than at any other time in the last 2,800 years.8

However, when considering nuisance flooding, it is often more helpful to think in terms of relative sea-level rise (RSLR). Although impacted by the thermal expansion and ice melt mentioned above, RSLR is more sensitive to vertical land motion, or the rise and fall of land masses.9 This VLM can result in sinking, or subsidence, as humans extract water, oil, and/or natural gas from under the land surface. As the land sinks, RSLR increases.

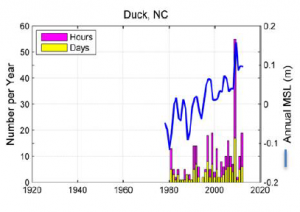

Changes in RSLR will lead to changes in tidal datums. Scientists typically use the tidal datum of mean sea level (MSL) as their reference point in describing changes in sea level.10 As seas rise, the gap between MSL and flooding thresholds, also called freeboard, shrinks. This means that it will take smaller and smaller meteorological or tidal events to result in the flooding and damage which were previously only caused by more extreme weather.11 In this figure from NOAA, it is easy to see how MSL (the blue line) at a Duck water level station has increased over the past couple decades. Note also the magenta and yellow bars, which represent hours and days of nuisance flooding, respectively.

Logically, areas which set their nuisance flooding threshold at a lower elevation will also experience more nuisance flooding events.12 This would appear to be the case in Beaufort and Wilmington, where nuisance flood thresholds are set at low elevations.13It is important to note that simply setting flood thresholds at a higher elevation is not a long-term solution: even if a future flood does not meet the elevation criteria to be officially categorized as a minor or nuisance flood, negative impacts will still occur. Flooding needs no official title to wreak havoc.

In essence, higher sea levels mean higher high tides, meaning that the flood threshold set by NWS is that much easier to surpass. In fact, the amount of times that the flooding threshold is overtopped in some areas, referred to as “exceedances“, may grow exponentially in the near future.14 The frequency with which exceedances occur has been increasing over time and in many cases, is accelerating.15 Higher seas will result in more exceedances while also allowing storm surges and high tides to move further inland, causing greater amounts of physical and economic damage.

What does this mean for North Carolina going forward?

As coastal climate change impacts continue to emerge, nuisance flooding will only become worse. According to NOAA, the amount of nuisance floods which occurred in the U.S. in 2015 was at least double the amount from 1995.16 In 2015, Wilmington saw a staggering 90 days of flooding, an all-time record for the city17 and an increase of 19 days as compared to 2014.18

Although the effect of changed tidal datums and storm impacts is often not readily visible to a coastal resident, changes in the frequency and severity of nuisance flooding likely will be.19 For example, by about 2030, RSLR will probably result in Duck facing extensive flooding from tides alone, no storms required.20 By 2045, Wilmington is predicted to be spending more than 5% of each year underwater, or more than 345 hours.21

Footnotes

[1] Sweet, William V. and Marra, John J. “2015 State of U.S. ‘Nuisance’ Tidal Flooding.” NOAA, Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS). 2016. 1.

[2] Tidal datums are also critical in the design of nautical charts and the drawing of marine boundaries delineating private property, state property, and even international borders.[3] “Tidal Datums.” NOAA, 15 Oct. 2013. Web. <https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/datum_options.html#NTDE>.

[4] United States. NOAA. Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS). Tidal Datums and Their Applications. Silver Spring, MD. 2000. 14.

[5] The duration of the NDTE also matches the moon’s node cycle (although that cycle technically lasts only 18.6 years).[6] NOAA. Tidal Datums and Their Applications. 2000. 3.

[7] United States. NOAA. Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS). Sea Level Rise and Nuisance Flood Frequency Changes around the United States. Silver Spring, MD. 2014. vi.

[8] United States. NOAA. Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS). Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States. Silver Spring, MD. 2017. 1.

[9] Ibid. 7.

[10] Sweet, William V., and Joseph Park. “From the Extreme to the Mean: Acceleration and Tipping Points of Coastal Inundation from Sea Level Rise.” Earth’s Future 2.12 (2014): 579-600. Web. <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014EF000272/full> . 579.

[11] Ibid. 580.

[12] NOAA. Sea Level Rise and Nuisance Flood Frequency Changes around the United States. 2014. 23.

[13] Ibid. 12.

[14] Sweet and Park. “From the Extreme to the Mean: Acceleration and Tipping Points of Coastal Inundation from Sea Level Rise.” (2014). 594.

[15] NOAA. Sea Level Rise and Nuisance Flood Frequency Changes around the United States. 2014. Vi.

[16] Sweet, William V. and Marra, John J. “2015 State of U.S. ‘Nuisance’ Tidal Flooding.” NOAA, Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS). 2016. 1.

[17] Ibid.

18 Sweet, William V. and Marra, John J. “2014 State of U.S. ‘Nuisance’ Tidal Flooding.” NOAA, Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS). 3.

[19] NOAA. Sea Level Rise and Nuisance Flood Frequency Changes around the United States. 2014. 1.

[20] Spanger-Siegfried, E., M.F. Fitzpatrick, and K. Dahl. 2014. Encroaching tides: How sea level rise and tidal flooding threaten U.S. East and Gulf Coast communities over the next 30 years. Cambridge, MA: Union of Concerned Scientists. 18.

[21] Ibid. 20.